In recent decades, treatment advances have helped people with cancer live longer and better lives. Scientific investments have led to breakthroughs not previously imaginable, such as the development of immunotherapies and precision medicines. However, treating people with serious diseases such as cancer is expensive. The direct medical costs of cancer reached $88 billion in 2014, 12.4 percent of which was attributed to drugs.

Given the costs of new treatments, the U.S. health care system faces unprecedented pressure to improve the efficient and appropriate use of health care products and services. Health care decision makers are challenging pharmaceutical manufacturers to demonstrate the value of their medicines, not just in terms of clinical efficacy but also in terms of economic and quality-of-life outcomes. As a result, there is growing interest in outcomes-based (or performance-based) contracting, which is intended to align pricing with a medicine’s observable clinical benefit. While definitions of outcomes-based contracts vary across the industry, common arrangements tie rebates to patient outcomes, rather than to volume. For example, the manufacturer agrees to provide a rebate to a payer if the observed performance of a specific medicine doesn’t reach the agreed-upon threshold. If the medicine performs as observed in clinical trials (or better), the payer does not receive a rebate.

Background

In 2015, Genentech (Note 1) (a drug manufacturer) and Priority Health (Note 2) (a nonprofit health plan) agreed to collaborate on an outcomes-based contract for Avastin ® (bevacizumab) in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We sought to move beyond the transactional nature of payer–pharma relationships to build a strategic relationship, ensuring that the right patients are on the right medication. Our ultimate intent was to improve patient outcomes. Philosophically, we agreed that payers may feel more comfortable with the cost of medicines that produce positive outcomes in clinically appropriate patients, and that there are situations in which manufacturers should share some financial risk when a medicine doesn’t work as well as expected. Our expectation was that a workable pilot contract might lay a foundation for demonstrating the potential benefits of outcomes-based agreements to patients, providers, payers, and manufacturers.

Key Considerations

We recognized and addressed five fundamental requirements for developing and executing an outcomes-based agreement.

Leadership commitment

Both parties must commit time and resources for design and implementation. Because outcomes-based contracts are still in their infancy, and much is undefined, manufacturers and payers should expect a period of trial and exploration until the contract terms are defined.

Medicine selection

Not all conditions and medications are good candidates for outcomes-based contracts. The selected medicine should have clearly defined outcomes that can be observed in a relatively short timeframe (preferably less than one year), obtained easily, and measured reliably and objectively. Medicines indicated for chronic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, or even some cancers may be less suitable if clinical endpoints are not measured consistently and objectively within a year.

Definitions and metrics

The ability to measure various outcomes, or “endpoints,” in a consistent and timely way varies widely among treatments. In oncology, for instance, progression-free survival (PFS) is an endpoint frequently used as a surrogate for overall survival in an accelerated or regular Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval pathway. Appropriate use of surrogate endpoints is highly dependent on multiple factors, such as effect size and duration, life expectancy based on the condition studies, benefits of other available therapies, and others. In the case of PFS, although it has not been statistically validated as a surrogate for survival in all settings, predictable measurement, smaller trial size, and shorter follow-up compared with overall survival studies have made it a desirable and frequent target in studies focused on appropriate tumor types.

Data issues

The operational requirements of outcomes-based contracts can be daunting. The payer is responsible for tracking an individual patient’s health status and for collecting and reporting patient-level longitudinal data. However, most payer systems cannot evaluate specific clinical and outcomes data. For example, a payer claims system may indicate when a patient discontinues a medication, but not why — a major stumbling block if PFS is the agreed-upon endpoint in the contract. Determining whether the discontinuation was due to clinical progression, toxicity, patient or provider preference, or some other reason often requires gaining access to the electronic health record (EHR), which many payers don’t have. Granting such access to payers can create privacy concerns.

Even with access to EHR data, payers may face challenges, such as missing data fields or pertinent data documented in nonreadable text fields. If a provider’s EHR system does not capture the desired endpoint, line of therapy, indication for which a drug is prescribed, or medication dose, it may be difficult for the payer to gain maximum benefit from the contract — either because of missing data or because of the overhead incurred in extracting data from text fields or chart reviews.

As these challenges suggest, it is important to balance specificity with simplicity. If complexity makes operationalizing the contract impractical or cumbersome, either the manufacturer or the payer may be unwilling to enter into an agreement.

Government price reporting

A manufacturer’s willingness to participate in value-based agreements can be limited by government price-reporting obligations. Medicaid’s “best price” rule, 340B ceiling prices, and Medicare’s calculation of average sales price (ASP) for medicines covered under Medicare Part B can be affected by the magnitude and scale of outcomes-based agreements. The degree of discounting under these types of agreements can effectively reduce a drug’s price to below the Medicaid benchmark, resulting in a “new” 340B price for manufacturers, and adversely affect ASP-based reimbursement for provider-administered medicines, even if these providers do not participate in or benefit from outcomes-based arrangements.

Genentech–Priority Health Pilot Design and Structure

The focus of the Genentech–Priority Health outcomes-based pilot was the first-line use of Avastin (bevacizumab) in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Under the terms of the agreement, we tied rebates to PFS, a key endpoint in the phase 3 clinical trial. The shorter the PFS in a given patient, the greater the rebate to Priority Health. If a patient remained progression-free on bevacizumab longer than six months (the median PFS outcome in the phase 3 trial of bevacizumab for this indication), Priority Health would not receive a rebate. Genentech and Priority Health agreed to measure PFS at the individual level rather than at the population level to expedite data capture and increase the timeliness of rebates. We agreed on a methodology for calculating and verifying PFS from claims, imaging, and EHR data.

In selecting this outcome measure, both parties had to be willing to make some assumptions. For example, we agreed to identify appropriate patients for inclusion based only on diagnosis codes. Although this criterion is not specific to type or stage of cancer, we agreed that if a patient had a diagnosis of lung cancer and was on bevacizumab, we could assume that it was for stage IV, metastatic NSCLC, consistent with the drug’s labeling. Although a prior authorization process could capture both stage and line of therapy, Priority Health does not require prior authorization for these purposes. We also agreed to assume first-line treatment if there was no chemotherapeutic agent within six months prior to the first date of infusion and no diagnosis of lung cancer within 60 days.

We rounded down the threshold for a rebate (six months of PFS) from the outcome of the clinical trial (a 6.2-month PFS advantage) for simplicity of executing a contract. For patients whose claims indicated that they were on bevacizumab for more than six months, we deemed the threshold met. For patients for whom the interval between the first dose and the last dose was less than six months, we agreed to establish the reason: toxicity, progression, or patient or provider preference to switch. If the patient was switched because of toxicity or disease progression, Genentech would rebate a portion of the drug cost to Priority Health. If the patient switched treatment because of provider or patient preference, Genentech would not provide a rebate to Priority Health.

To assess the reason for discontinuation, Priority Health accessed EHR data through a regional health information exchange, Great Lakes Health Connect. The parties agreed that an imaging study recorded in the EHR indicating, for example, “The patient has progression by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria” would be acceptable evidence of disease progression. If no imaging study was available, then Priority Health reviewed oncology office, infusion center, or inpatient EHRs. In the absence of any electronic records, Priority Health obtained records from the treating oncologist to assess what prompted the discontinuation. Priority Health agreed to commit the internal resources necessary to locate these data. Genentech supported Priority Health’s efforts with a dedicated team of medical and privacy professionals.

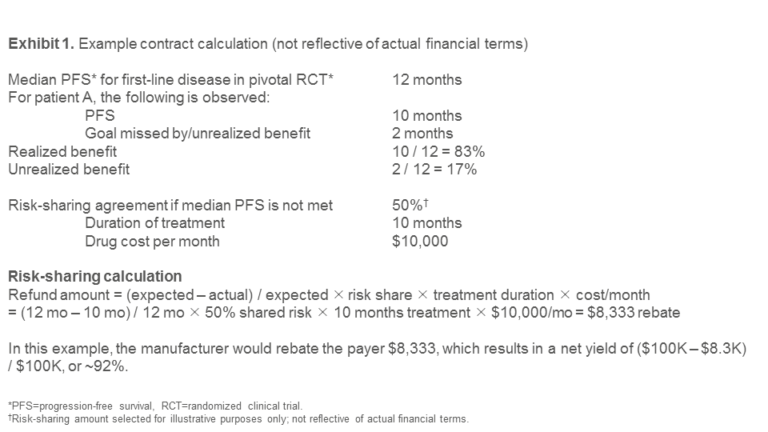

Each rebate was directly proportional to the magnitude of the difference between the actual and expected PFS. Exhibit 1 shows an illustrative calculation to demonstrate how such an agreement could be structured. (Note: Discount values shown below are for illustrative purposes only and are not feasible in today’s environment due to the government price-reporting obligations referenced earlier.)

With regard to the impact of this rebate on government price reporting, the effect of the Genentech–Priority Health pilot contract is finite, and we deemed it manageable, given its size and scale. However, the potential impact on government prices for certain drugs may be a deterrent in future large-scale outcomes-driven contracts.

Conclusion

Outcomes-based agreements are a natural extension of a health care delivery-and-reimbursement environment that is moving toward value. With provider organizations taking increasing accountability for both costs and outcomes, it is becoming incumbent upon manufacturers to demonstrate the economic, clinical, and quality-of-life benefits of their medicines. The pilot described here was successful in that Genentech and Priority Health both learned how to overcome clinical, operational, and contractual challenges and demonstrated that this type of agreement is feasible. Genentech and Priority Health believe pilots like the one explored here are the right way forward.

In providing resources to advance this work, we are creating strategic relationships that are essential to today’s focus on value. The success of these types of efforts depends on leaders across stakeholder groups who are willing to champion the work, take on a learning mind-set, and share a commitment to being part of a solution to health care cost, data, and access issues. As such, we measured the success of this pilot in operational learnings, as opposed to immediate financial benefits. Although not a panacea, outcomes-based contracts may be a useful tool in aligning cost and value, driving health care efficiency, and ensuring that appropriate patients benefit from innovative medicines.

Such efforts can have impact only if scale can be achieved. Although pilot agreements such as the one described here are feasible, large-scale agreements will ultimately generate broad industry change. The inherent complexities of outcomes-based contracts should not serve as a deterrent. Rather, they should compel all involved entities, both public and private, to collaborate on and devote resources to addressing cost, data, and access challenges. No one manufacturer, payer, or provider can single-handedly make outcomes-based contracting a reality. However, continued collaboration and government entities’ support will be critical in reaching a long-term solution.

Note 1

Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, is a biotechnology company that discovers, develops, manufactures, and commercializes medicines to treat patients with serious or life-threatening medical conditions.

Note 2

Priority Health is a Michigan-based nonprofit health plan with a portfolio of health benefit options for employer groups and individuals, including Medicare and Medicaid plans.