On April 13, 2017 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released the final rule designed to “improve the risk pool and promote stability in the individual insurance market” for 2018. The rule finalizes the provision from the proposed rule (82 FR 10980) that reduces the length of the 2018 open enrollment period from three months (November 1, 2017–January 31, 2018) to 45 days (November 1, 2017–December 15, 2017) to “reduce opportunities for adverse selection.”

Using weekly enrollment data, we find that such a reduction may decrease enrollment by “healthy procrastinators” and plan switching among re-enrollees. Nearly 60 percent of new enrollments (59.5 percent) and more than one-third of those switching from a subsidized platinum-level plan to a lower metal level (35.6 percent) did so during the second half of a three-month long open enrollment period in 2015.

Open Enrollment Periods

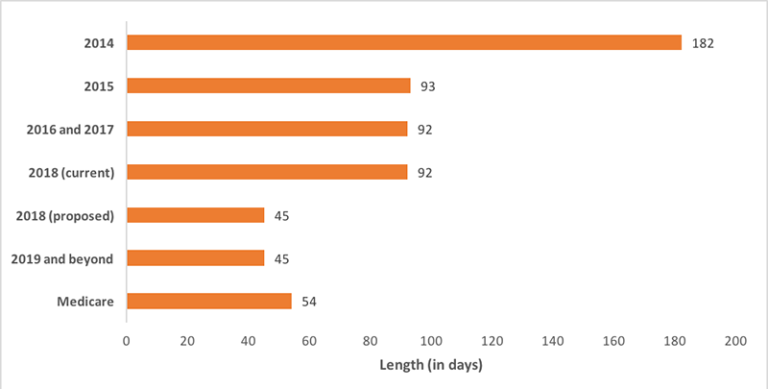

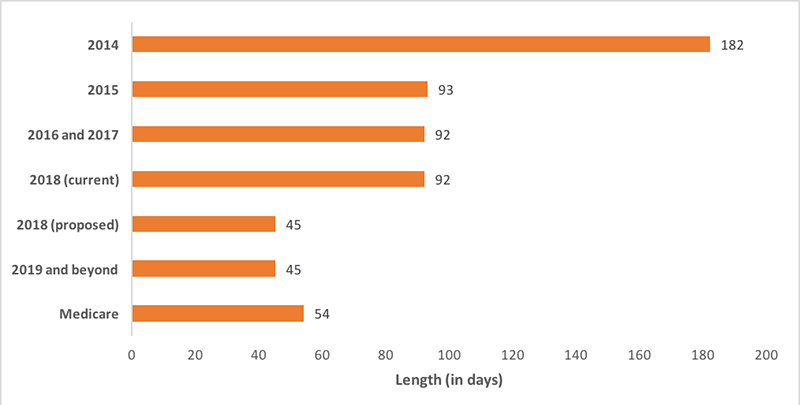

This reduction would make the open enrollment period considerably shorter than that of previous years and for Medicare supplement and Part D prescription drug plans (54 days) (Exhibit 1), which are only add-ons to existing coverage and therefore much less complex than choosing from a menu of comprehensive health plans. Though this change could be interpreted as an effort by the Trump administration to depress enrollment, such a reduction was already legislated for 2019 and beyond (45 CFR 155.410). However, with the intensity of the rhetoric about the repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and recent failure by the House of Representatives to pass the American Health Care Act (AHCA), the proposed rule to shorten the open enrollment period for 2018 may create additional uncertainty for consumers. This is particularly true if efforts to diminish outreach and enrollment assistance late in the 2017 open enrollment period are carried forward to 2018.

A shorter open enrollment period would—by definition—reduce the length of time during which a new diagnosis could encourage enrollment. However, it is unclear whether longer enrollment windows increase risk for health insurers through adverse selection or decrease risk by providing greater opportunities for enrollment by so-called “healthy procrastinators.” Express Scripts, a pharmacy benefits manager, reported that later enrollees during the five-month long open enrollment period for 2014 were generally younger and healthier than those enrolling earlier, contradicting the idea that those enrolling later are necessarily a worse risk for insurers.

Under the ACA, fewer individuals would be expected to be new enrollees in exchange plans over time as the individual mandate and premium tax credits encourage continuous enrollment, though failure to enforce the mandate (as has been suggested) could have an impact if clearly communicated to consumers. Of over 9 million enrollees during the 2017 open enrollment period through Healthcare.gov, approximately two-thirds were re-enrollees. We use data obtained from a state-based exchange to explore the potential impact of a shorter open enrollment period on both new and re-enrollees. We also describe characteristics of those who remained uninsured after the initial open enrollment period to explore the potential for adverse selection by new enrollees.

Enrollment Patterns By New And Re-Enrollees

Kentucky had the largest decline in the rate of adult uninsured from 2013 to 2016, making it an ideal setting for observing enrollment patterns. We obtained weekly enrollment reports from the Office of the Kentucky Health Benefit Exchange through a state public records request. These reports were originally submitted by the state to the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight (CCIIO) at CMS. The state-based exchange in Kentucky (kynect) was in operation through the 2016 open enrollment period before then newly elected Governor Matt Bevin decided to transition the state to Healthcare.gov beginning in 2017. We utilize data from the 2015 open enrollment period to evaluate enrollment patterns by re-enrollees and new enrollees. To the extent that outreach and availability of enrollment assistance may vary across states, other states may display different patterns of enrollment.

A majority of those who enrolled during the 2015 open enrollment period were re-enrollees (74.2 percent) and over 90 percent of re-enrollments took place in the first week (92.1 percent), varying only slightly by whether an enrollee was eligible for financial assistance (92.5 percent) or not (91.3 percent) (Exhibit 2). Re-enrollment was automatic if the existing policy or an approved substitute was available, but enrollees could change their plan selection during the remainder of the open enrollment period. About half of those who were initially re-enrolled in platinum-level plans and receiving financial assistance switched to a lower metal level plan (49.4 percent). Of these switches, over one-third (35.6 percent) took place in the second half (weeks 7 through 13) of the open enrollment period. By reducing the length of open enrollment, inertia may result in consumers staying in less than optimal plans (e.g., too comprehensive for their needs, more expensive than a comparable competing plan), blunting the effect of insurer competition.

Approximately one-quarter of new enrollments took place in the final week of open enrollment (25.1 percent) (Exhibit 3). Those eligible for financial assistance were slightly more likely to delay enrollment until the final week of enrollment (26.2 percent) compared to those not receiving financial assistance (22.3 percent). This jumps up to more than one-third over the final three weeks (36.1 percent) and nearly 60 percent over the second half of the open enrollment period (59.5 percent). New enrollees made up approximately one-quarter of total enrollment (25.8 percent) during the 2015 open enrollment period. Whether new enrollees in 2015 are a higher risk for insurers than their previously enrolled counterparts remains unknown. Some may have been purposeful in their decision not to enroll for 2014 given that special enrollment periods can be granted year-round for qualifying life events, such as loss of a job (and associated employer-based coverage), birth of child, et cetera. Then, the decision to enroll in subsequent open enrollment periods could be evidence of adverse selection.

Characteristics Of Potential New Enrollees In 2015

To explore this issue, we used data from the Kentucky Health Issues Poll to identify characteristics of potential new enrollees for 2015 — those uninsured in late 2014. This telephone-based survey was administered by Institute for Policy Research at the University of Cincinnati on behalf of Interact for Health and the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. The 2014 wave included a random sample of 1,597 adult Kentuckians and was conducted in the weeks leading up to the 2015 open enrollment period (October 8, 2014–November 6, 2014). The data were weighted to be representative of the adult population of the state.

Among those who reported being currently uninsured—potential new enrollees in exchange plans—a majority self-reported being in at least “good” health (73.8 percent), were currently employed at least part-time (64.2 percent), and were at or above 138 percent of the federal poverty level (67.1 percent) — the income limit for Medicaid after expansion. A majority were 45 years of age or under (18-24 — 25.1 percent, 30-45 — 32.9 percent, 46-64 — 35.0 percent, ³65 — 7.0 percent) with a nearly even split by gender (male — 51.0 percent, female — 49.0 percent). Avoiding adverse selection is an obvious concern for insurers, but limiting enrollment periods could also potentially reduce enrollment by younger and/or healthier individuals — a group critical to balancing the risk pool and lowering (or at least slowing the growth of) premiums in exchange plans.

Although our findings are descriptive, they suggest that reducing the length of the open enrollment period in 2018 may cause as much or more harm for consumers (e.g., reduced plan switching among re-enrollees, lower enrollment among those eligible but previously uninsured) than any potential reduction in adverse selection for insurers. If CMS has data to support the motivation described in the rule, sharing it would help engender support for this rule as a tool to stabilize the exchanges and encourage insurer participation.

Exhibit 1: Comparison of open enrollment period lengths

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

Exhibit 2: Weekly re-enrollment by financial assistance

Source: Office of Kentucky Health Benefit Exchange, 2015 open enrollment period (November 15, 2014–February 15, 2015)

Exhibit 3: Weekly new enrollment by financial assistance

Source: Office of Kentucky Health Benefit Exchange, 2015 open enrollment period (November 15, 2014–February 15, 2015)

Authors’ Note

This research is supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.