Average wholesale prices (AWPs) have long been recognized as a flawed payment benchmark because they are list prices that do not reflect the real-world prices available in the marketplace. For that reason, a common joke in the drug pricing world panned AWP as “Ain’t What’s Paid.”

After years of reports from the Office of Inspector General (OIG), analysis from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), and litigation that highlighted the flaws in AWPs, Congress required in 2003 that reimbursement of Part B drugs be set 106 percent of their average sales price (ASP). ASPs are calculated based on the prices at which manufacturers sell the drugs to wholesalers and other private supply chain participants (with some exceptions, such as pharmacies participating in the 340B drug discount program). Following the implementation of the ASP law in 2005, reimbursement amounts for most individual Part B drugs became much better aligned with costs.

The birth of ASP for Part B is likely familiar to Health Affairs readers. However, likely not well known is that about two-to-three dozen durable medical equipment (DME) infusion drugs were exempted from the switch to ASP; instead, the law set reimbursement for these drugs at their respective AWPs from October 2003. The reasons why Congress exempted DME infusion drugs are unclear, but the consequences have been well documented in several recent OIG reports.

OIG studies have repeatedly shown that Medicare’s reimbursement methodology for DME infusion drugs has resulted in payment amounts that bear little relationship to actual market prices. For drugs whose costs have remained significantly below their October 2003 AWPs, Medicare and its beneficiaries have incurred substantially excessive payments. In contrast, for DME infusion drugs that have seen their costs surpass those October 2003 AWPs, Medicare reimbursement has not kept pace with actual costs and, in some cases, Medicare beneficiaries now face difficulties in finding providers willing to accept Medicare payment for the drugs. This post examines these issues and suggests a path forward for policymakers.

What Are DME Infusion Drugs?

Infusion therapy is often provided in the home, rather than in inpatient settings, to reduce costs associated with inpatient care and to maintain patient convenience and comfort. In general, external and implantable pumps used in home infusion therapy are covered by Medicare under the DME benefit. Medicare Part B covers the drugs used in home infusion therapy under its DME benefit if (1) the drug is necessary for the effective use of a covered external or implantable infusion pump and (2) the drug being used with the pump is itself reasonable and necessary for the patient’s treatment.

From April 2013 through September 2014, six drugs accounted for 97 percent of the $712 million that Medicare spent on DME infusion drugs (listed in order of expenditures):

- treprostinil: indicated for pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Hizentra®: indicated for primary humoral immunodeficiency

- milrinone lactate: indicated congestive heart failure

- Gammagard®: indicated for primary immunodeficiency

- epoprostenol: indicated for pulmonary arterial hypertension

- insulin: indicated for diabetes

Patients obtain DME infusion drugs with a doctor’s prescription. Although some of these drugs may be available through traditional retail or mail pharmacies, others are typically filled by specialty suppliers such as home infusion pharmacies or diabetic supply companies. Medicare beneficiaries are responsible for 20 percent of the cost of these drugs through coinsurance.

The Dangers Of Excessive Payments: Milrinone Lactate

The reliance on an AWP-based payment methodology has cost the Medicare program hundreds of millions of dollars. For many products, Medicare’s payment amount is more than double the cost of the drug, with some drugs seeing an even larger spread. The most telling example is milrinone lactate.

Suppliers of milrinone lactate (generally home infusion pharmacies) have benefited from years of being reimbursed at amounts considerably higher than their costs for the drug. From 2006 through 2015, suppliers paid an average of $1.89 to $5.51 per five milligrams (mg) of milrinone lactate, while Medicare payment has remained at $51.58. The 357 suppliers who Medicare paid for milrinone lactate in 2015 could each expect to net about $64,000 annually per beneficiary based on the difference between payment amounts and acquisition costs; 35 of these suppliers each would capture over $1 million a year above cost, with the top supplier netting approximately $7 million. A portion of this differential comes from Medicare beneficiaries, given their 20 percent coinsurance responsibility.

The substantial difference between Medicare payment amounts and supplier acquisition costs for milrinone lactate creates incentives for abuse. In 2015, a Medicare DME contractor conducted two prepayment reviews involving approximately 175 milrinone lactate claims. The reviews, which required suppliers to submit supporting documentation prior to receiving Medicare payment, highlight the extent of overutilization and improper billing that may be occurring, with charge denial rates (i.e., the percent of charges found to be billed in error) of approximately 75 percent. Primary reasons for denying payment included: (1) claims not meeting coverage criteria; (2) missing, incomplete, or invalid written orders; and (3) proof-of-delivery issues.

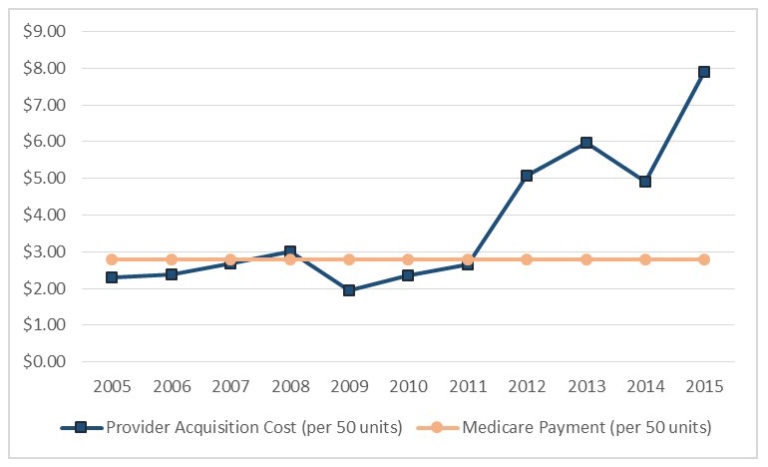

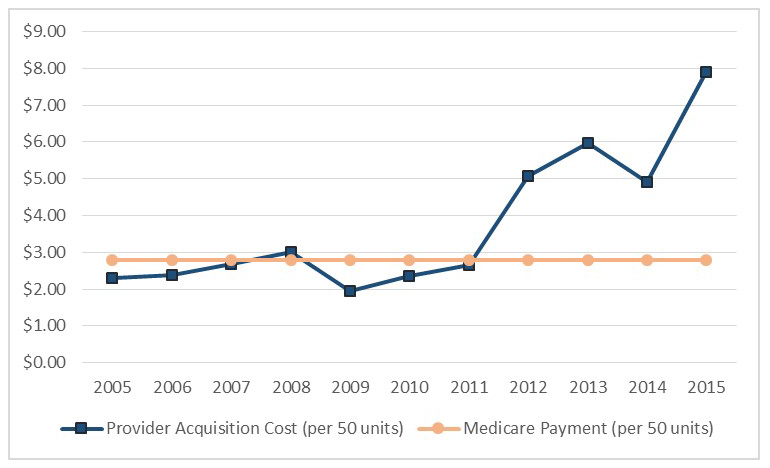

The Dangers Of Payment Below Costs: Insulin

In contrast to milrinone lactate, OIG found that a number of other DME infusion drugs—most notably pump-administered insulin—have seen their acquisition prices climb above the fixed AWP used to set reimbursement. In 2012, the prices suppliers paid to acquire insulin increased substantially, as reflected in Figure 1. By the fourth quarter of 2015, the average cost of insulin had risen to $7.91 per 50 units, almost triple its cost four years earlier. Medicare’s payment amount—set by law at 95 percent of the AWP from October 2003—was just $2.80 for the same number of units. If the average cost of insulin holds at $7.91 through 2016, Medicare suppliers could face an annual net loss of $30 million on the drug, or approximately $2,100 per beneficiary receiving pump-administered insulin.

Figure 1: Medicare Payments for Insulin do not Reflect Acquisition Cost Increases for the Drug

Source: OIG analysis of CMS ASP and payment amount data for pump-administered insulin, 2016.

Notes: Costs and payment amounts are from the fourth quarter of each year. Acquisition costs were estimated using ASPs.

Several sources report that beneficiaries are having difficulties finding suppliers who accept Medicare payment for pump-administered insulin. For example, in the 2013 CMS Medicare Ombudsman’s report to Congress, the agency stated that it had heard from beneficiaries who could not find an insulin supplier willing to accept Medicare after their previous suppliers ceased accepting Medicare for the drug. One newspaper article profiles a Medicare beneficiary who resorted to buying insulin on Craigslist after his previous suppliers ceased taking Medicare payment for the drug.

In July 2010, OIG and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) received a letter from one of Medicare’s largest suppliers of pump-administered insulin. The supplier claimed that “[w]ithout swift action to correct these inequitable policies, [we] will have no choice but to stop supplying rapid-acting insulin to people with Medicare who use insulin pumps.” Other large suppliers appear to have reached the same conclusion. In 2011, three companies (including the company referenced above) supplied 70 percent of the insulin paid for under Medicare Part B. Just four years later, these companies didn’t have a single paid claim for the drug, meaning that more than 10,000 Medicare beneficiaries had to find new suppliers — suppliers willing to incur a loss when providing insulin.

How To Address The Problems

OIG studies have repeatedly shown that Medicare’s reimbursement methodology for DME infusion drugs has resulted in payment amounts that bear little relationship to actual market prices. When Medicare payments greatly exceed acquisition costs, as is the case with milrinone lactate, there may be incentives for providers to over-utilize a particular drug, further increasing excessive Medicare payments. In contrast, under-reimbursement for drugs like pump-administered insulin has led to access issues, as some suppliers ceased providing insulin to Medicare beneficiaries.

To ensure that payment amounts for DME infusion drugs more accurately reflect acquisition costs, OIG has recommended that the CMS either (1) seek a legislative change requiring that DME infusion drugs be paid using the ASP-based methodology or (2) include DME infusion drugs in the next round of the competitive bidding program, in which suppliers submit bids to become Medicare contract suppliers and payment amounts resulting from the bids replace current fee-schedule payment amounts.