The Trump Administration and Republicans in Congress are fond of saying that the ACA is collapsing under its own weight, and that the exchanges are exploding (or imploding, depending on the day).

Most of the exchanges headed into 2017 on fairly stable footing though. Whether that will continue to be the case in 2018 is still unknown – largely because of the considerable uncertainty that the Trump Administration and Congressional Republicans have introduced to the market this year.

Most of the exchanges headed into 2017 on fairly stable footing though. Whether that will continue to be the case in 2018 is still unknown – largely because of the considerable uncertainty that the Trump Administration and Congressional Republicans have introduced to the market this year.

There are undoubtedly some problems. Insurer exits from the exchanges were commonplace at the end of 2016, and unsubsidized premiums in the individual market increased by an average of 25 percent for 2017. (Nearly 83 percent of exchange enrollees nationwide are receiving premium subsidies and those subsidies grew in 2017 to keep pace with the rate increases. But for the other 17 percent of exchanges enrollees – and for everyone who buys coverage off-exchange – health insurance premiums are sharply higher in 2017 than they were in 2016.)

While the individual market might not be exploding (not yet, at least), Republican talking points about the problems in the individual market are not entirely without merit. But the story of Obamacare’s problems is not complete unless we take a look back over the last several years and look at all the ways Republican lawmakers, governors, and pundits – and now the Trump Administration – took steps to deliberately weaken the Affordable Care Act.

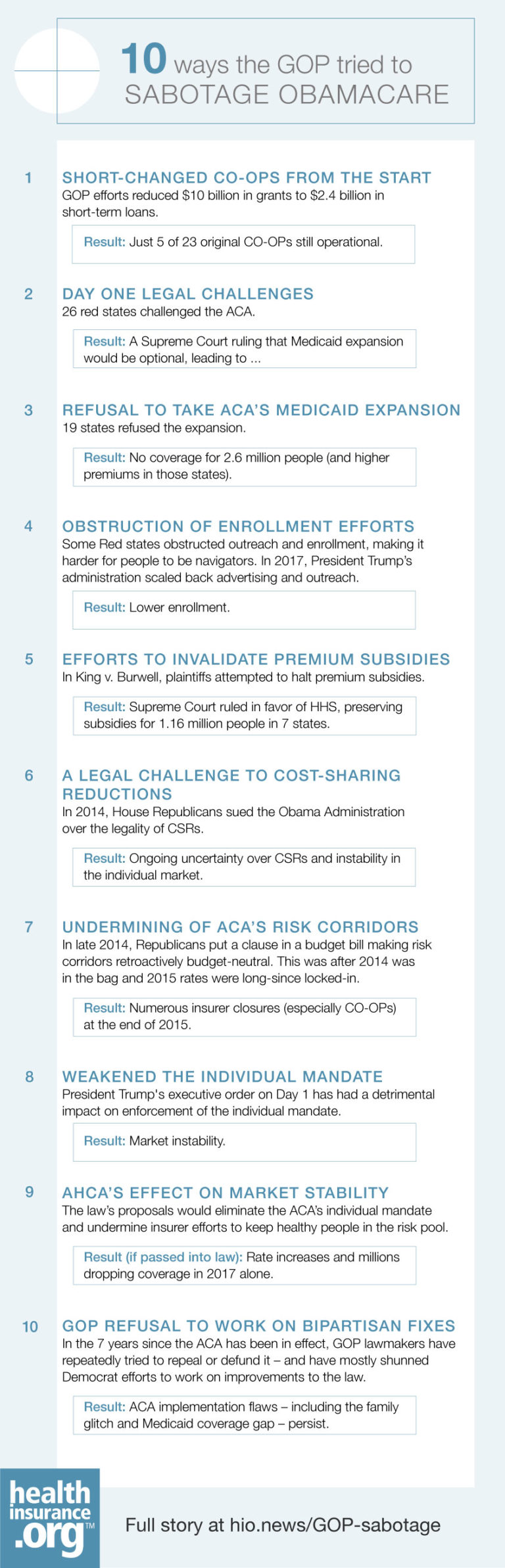

1. CO-OPs short-changed from the start

Let’s start by considering the ACA’s Consumer Operated and Oriented Plans, or CO-OPs. Early drafts of the ACA called for $10 billion in federal grants for the CO-OP program. But insurance lobbyists and conservative lawmakers insisted on $6 billion in loans instead of $10 billion in grants, restrictions limiting CO-OPs to the individual and small-group market (and not the more stable and profitable large-group market), and limitations stating that the federal loan money could not be used for marketing.

The ACA passed in 2010 and the CO-OPs were to be up and running in the fall of 2013, in time for the first open enrollment period. But during 2011 budget negotiations, $2.2 billion was cut from the CO-OP funding. And then during the “fiscal cliff” negotiations at the end of 2012, another $1.4 billion in CO-OP loan funding was eliminated.

So instead of $10 billion in grants, the CO-OPs got $2.4 billion in short-term loans, and a slew of restrictions on their business practices. Some of those restrictions were relaxed in 2016 under new HHS regulations, but it was too little, too late for most CO-OPs.

As of 2017, only five of the original 23 CO-OPs are still operational. (Evergreen Health in Maryland is technically still operational, but it’s in the process of being acquired and converted to a for-profit insurer.)

2. Day One legal challenges

On March 23, 2010, the same day the ACA was signed into law, attorneys general from 14 states began the process of challenging the ACA’s individual mandate via the court system. A total of 26 states eventually joined in the lawsuit, which went all the way to the Supreme Court.

In June 2012, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of the individual mandate, but ruled that the federal government could not withhold Medicaid funding from states that didn’t expand Medicaid. This had the effect of making the ACA’s Medicaid expansion optional, which has in turn hobbled the ACA’s progress in many states.

3. Refusal to take ACA’s Medicaid expansion

The ACA scheduled Medicaid expansion to take effect at the beginning of 2014. But at that point, half the states had opted against expansion, despite the fact that the federal government paid the full cost of expansion for the first three years (and nearly all of it after that). Even now, in 2017, there are still 19 states that have not expanded Medicaid.

That obviously has a negative impact on people living in poverty, but it’s also deleterious to the individual insurance markets in those states.

Medicaid expansion allows adults with income up to 138 percent of the poverty level to enroll in Medicaid. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, however, the state’s regular eligibility guidelines apply, and generally prevent able-bodied childless adults from enrolling, regardless of how low their income is.

And ACA premium subsidies in the exchanges don’t apply to people with income below the poverty level, as those applicants were supposed to be eligible for Medicaid instead. So in 18 of the 19 states that have not expanded Medicaid (all but Wisconsin), there is no financial assistance available for people with income below the poverty level who don’t qualify for Medicaid based on each state’s strict eligibility guidelines. That creates a coverage gap, into which 2.6 million people currently fall.

Those 2.6 million people should have coverage, according to the ACA. But 26 states sued the Obama Administration to block the ACA, and the result was that Medicaid expansion became optional. Nineteen states still haven’t expanded Medicaid, despite the fact that their decisions leave 2.6 million people with no realistic access to health insurance coverage.

But what about the people with income between 100 percent and 138 percent of the poverty level? In states that expanded Medicaid, those individuals are eligible for Medicaid. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, people in that income bracket are eligible for substantial premium subsidies in the exchange, but not Medicaid.

An August 2016 HHS Research Brief indicates that in states that have not expanded Medicaid, people with income between 100 percent and 138 percent of the poverty level account for nearly 40 percent of total exchange enrollment – the highest percentage of any income category in those states. In contrast, people at that income level make up just 6 percent of the exchange enrollment in states that have expanded Medicaid.

Lower incomes are correlated with poorer health. And in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid, a substantial percentage of the population enrolled in exchange plans have incomes below 138 percent of the poverty level. The result is an individual market risk pool that has overall worse health than it would have if Medicaid had been expanded. Refusal to expand Medicaid is one of the factors that drives premiums up in the individual market.

4. Obstruction of enrollment efforts

Most states have opted to let HHS do the heavy lifting on exchange creation. Although there has been some shifting over the years, there are currently just 12 fully state-run exchanges (11 states and DC). The rest of the states use HealthCare.gov, either as part of the federally run exchange, or as an enrollment platform for a federally supported state-based exchange.

In states that use the federally run exchange, HHS provides funding for navigators to assist with the outreach and enrollment process. This is local, community-based help that particularly benefits lower-income people, and it’s funded by the federal government. Sounds like a win for the states, right?

But by January 2014, laws had been passed in 17 states that restricted navigators’ ability to help residents understand and enroll in the new plans. Some of those laws have since been blocked by the judicial system – Missouri’s, for example – but quite a few red states took it upon themselves to hamper their residents’ access to people and organizations who could help them make sense of the new insurance rules and plans.

Fast forward to January 2017. Trump was inaugurated 11 days before the end of the 2017 open enrollment period. And in the final week of open enrollment, the federal government scaled back advertising and outreach for HealthCare.gov, including pulling some ads for which payment had already been made. The result? Enrollment declined year-over-year in HealthCare.gov states, but grew in states that run their own enrollment platforms. This is particularly troubling for the stability of the insurance pools, because the last-minute stragglers who sign up at the end of open enrollment tend to be young, healthy people – exactly the people who are needed in the risk pool to keep it stable.

5. Efforts to invalidate premium subsidies

In King v. Burwell (formerly King v. Sebelius), plaintiffs argued that premium subsidies could not legally be distributed in states that didn’t establish their own health insurance exchanges. The Supreme Court ruled in the government’s favor in 2015, upholding the legality of premium subsidies in every state.

It’s notable, however, that Indiana, Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, Nebraska, South Carolina, and West Virginia all joined amicus briefs in support of the plaintiffs in King v. Burwell. Those states – all of which use the federally run exchange – supported the idea that premium subsidies should not be available in states that use the federally run exchange.

If the challengers had won, the individual mandate penalty would no longer have applied to most exchange enrollees in states that use the federally facilitated exchange, as coverage would not be considered affordable without the premium subsidies. And the employer mandate penalty would also not have applied, since it’s triggered when employees receive subsidies in the exchange.

But there are 1.16 million people in those seven states who are receiving premium subsidies in 2017. Not only would their subsidies no longer be available had the King v. Burwell plaintiffs prevailed, but without premium subsidies, the individual market would likely have collapsed altogether in states that didn’t run their own exchanges.

6. A legal challenge to cost-sharing reductions

The ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies are an essential part of making health care accessible for lower-income Americans. For people with incomes up to 250 percent of the poverty level, cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) are automatically added to silver plans, making the coverage much more robust than it would otherwise be.

The federal government reimburses health insurers for the additional coverage provided by the CSRs; those reimbursements totaled $7 billion in 2016. But in 2014, House Republicans, led by then-Speaker John Boehner, filed a lawsuit against the Trump Administration, challenging the executive branch’s authority to reimburse insurers for CSRs, as they had not specifically been appropriated by Congress.

In 2016, a district court sided with House Republicans. But the ruling was stayed to allow the Obama Administration to appeal, and CSR reimbursements have continued to flow to insurers ever since. The case took on a new twist when the Trump Administration took over, as it’s now House v. Price – House Republicans versus a Republican administration – and it’s been pended throughout the first part of 2017.

The Trump Administration has presented mixed messages in terms of whether CSRs will continue to be paid. In April, Trump even indicated that he would consider holding CSRs hostage in order to get Democrats to negotiate on health care reform.

The uncertainty surrounding CSRs has been repeatedly cited by insurers in their concerns about the stability of the individual markets. When Anthem cautiously indicated in April that they would continue to offer exchange plans in 2018, they noted that if the CSR situation is not resolved by June, they will reconsider their participation and/or substantially increase premiums for 2018.

This has been the same refrain from insurers all across the country this spring. And instead of working to stabilize the individual market by resolving the issue, the Trump Administration and Congressional Republicans have continued to drag it out, further destabilizing the individual market.

7. Undermining of ACA’s risk corridors

Risk corridors were a three-year program designed to keep the individual markets stable during the early years of ACA compliance. The idea was to take money from insurers that ended up with lower-than-expected claims, and send it to insurers that ended up with higher-than-expected claims.

And if insurers with higher-than-expected claims needed to be reimbursed more than the amount contributed by insurers with lower-than-expected claims, HHS was going to make up the difference. This was clarified in the 2014 Benefit and Payment Parameters, finalized in 2013. On the flip side, if insurers had done exceedingly well, HHS would have been able to keep the excess funding. Obviously that didn’t happen.

Then in late 2014, Republican lawmakers, led by Senator Marco Rubio, added language to a must-pass budget bill (Cromnibus) that retroactively made the risk corridors program budget neutral. This was after 2014 coverage had been provided for nearly the full year, and after 2015 open enrollment was already underway, with rates long-since locked-in.

Claims were indeed higher than expected in 2014. When the dust settled, carriers with higher-than-expected claims were owed a total of $2.87 billion, while carriers with lower-than-expected claims only contributed $362 million to the program. HHS took that money – which they could no longer supplement with federal funding due to the December 2014 Comnibus Bill – and spread it around to all the insurers that were owed money, but they were only able to pay them 12.6 percent of what was owed.

The 2015 risk corridor results were similarly bleak.

Large insurers were mostly able to weather this setback. But smaller insurers, and particularly the start-up CO-OPs, were not.

8. Trump’s executive order

On January 20, within hours of his inauguration, Trump signed his first executive order. The order directs federal agencies to

“exercise all authority and discretion available to them to waive, defer, grant exemptions from, or delay the implementation of any provision or requirement of the Act that would impose a fiscal burden on any State or a cost, fee, tax, penalty, or regulatory burden on individuals, families, healthcare providers, health insurers, patients, recipients of healthcare services, purchasers of health insurance, or makers of medical devices, products, or medications.”

The IRS soon reversed course on their previous plans to stop accepting “silent” returns that didn’t answer the “Did you have health insurance?” question. To be clear, the ACA penalty remains in effect for people who don’t have health insurance. But Trump’s executive order makes it easier for people to get around the penalty, simply because the IRS has been directed to do whatever they can, within the confines of current law, to minimize penalties.

In April 2017, HHS finalized a market stabilization rule aimed at propping up the individual insurance market via new regulations. But time and again, insurers have repeated that two of their biggest concerns are certainty with regards to ongoing funding for CSRs, and enforcement of the individual mandate. Neither of these are addressed by the market stabilization rule, and indeed, the Trump Administration has done the opposite of what insurers need on both issues.

9. AHCA’s effect on market stability

The House of Representatives has also worked to undermine the individual mandate via the American Health Care Act (AHCA) that they passed in early May.

The legislation would eliminate the individual mandate penalty retroactively to the start of 2016. And while it would instead institute a 30 percent rate increase (or health-status underwriting in states that opt for that) for people who don’t maintain continuous coverage, that provision wouldn’t take effect until after the 2018 open enrollment period is complete.

As passed by the House, the AHCA undermines insurers’ efforts to keep healthy people in the risk pool. Unsurprisingly, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that 4 million people would drop coverage in 2017 if the AHCA were to pass. Half of them are in the individual market, despite the fact that less than 6 percent of the U.S. population has coverage in the individual market.

Fewer healthy people in the risk pool results in further market destabilization. And there is no doubt that the people who would drop coverage in 2017 if the AHCA were to be enacted are currently healthy; sick people don’t voluntarily drop their health insurance.

10. GOP refusal to work on bipartisan fixes

The ACA has been in effect for seven years, and Republican lawmakers have been trying to repeal or defund it for seven years. (You can see some of their efforts here.) But they have been mostly unwilling to work together with Democrats to make any significant changes to the ACA to make it work better.

It’s true that the 21st Century Cures Act – which passed in late 2015 – had bipartisan support and allows small businesses to reimburse employees for the cost of individual market health insurance. This had previously been prohibited under guidance that HHS and the DOL had finalized in 2013, as part of their work to implement the ACA.

But other fixes that could have been made to the ACA never got off the ground. The family glitch has persisted, as has the Medicaid coverage gap (granted, fixing either of them would have been expensive, which is why the family glitch exists in the first place).

Republican lawmakers could have worked with Democrats to appropriate funding for cost-sharing reductions in 2014 – or anytime since then – rather than suing the Obama Administration.

Nothing would have changed in terms of cost outlays, since the federal government has continued to fund CSRs. But the individual market would certainly be much more stable now if lawmakers had opted to fix the problem instead of bringing a lawsuit over it.

The individual market has struggled. Thank the GOP.

Nobody is arguing that everything is fine in the individual market. But there have been signs in early 2017 that it has turned corner and is heading towards a stable equilibrium.

For that to happen, however, Congressional Republicans and the Trump Administration would have to commit to funding CSRs for the foreseeable future, vigorously enforce the individual mandate, and work at a state and federal level to ensure that people have access to enrollment assistance in every area of the country. Given the GOP’s unceasing efforts to drag down the Affordable Care Act so far, that would be remarkable – nay, miraculous.