As part of our mission to improve New Jersey’s health care delivery systems and reduce the costs of care for its underserved populations, The Nicholson Foundation has been working to strengthen primary care in the state’s safety-net system. Central to this effort is support for the integration of behavioral health care (substance use and mental health treatment) into primary care settings.

With the explosion of the prescription opioid crisis in the past several years, and the concomitant awareness of the role of primary care providers in inadvertently contributing to it, this integration work has become urgent and essential.

Pain is a common symptom reported by primary care patients—40 percent report pain as their chief complaint. However, despite sparse evidence that opioid pain relievers confer long-term benefits and evidence that they pose a significant risk of addiction or even death from unintentional overdose, they are often used to treat chronic noncancer pain. As many as one in four people who receive long-term opioid treatment from their primary care provider become addicted. A Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data showed that in 2014, opioids caused 28,647 overdose deaths nationally and 728 in New Jersey.

For those who become dependent on opioids, the substance use problem is often compounded by co-occurring mental health conditions. In New Jersey, as in many other states, limited behavioral health treatment capacity makes it difficult for those dependent on opioids to access adequate and timely care.

As a result of the alarming toll of the prescription opioid crisis in New Jersey, The Nicholson Foundation felt compelled to act. However, we wanted to act in a strategic way that dovetailed with and reinforced our broader efforts to improve New Jersey’s safety-net primary care system. Consequently, we looked to support a care model that would:

- offer primary care providers (PCPs) evidence-based pain management strategies so they could reduce inappropriate prescribing of prescription pain medications,

- improve PCPs’ understanding of the role of behavioral health in both pain management and the treatment of physical health conditions so they could take a more active role in managing behavioral health conditions,

- train and support PCPs in using medication-assisted treatment for their opioid-dependent patients, and

- provide coaching to clinical and administrative staff to facilitate the adoption of practice-wide improvement strategies to support PCPs in providing state-of-the-art pain care.

In the years leading up to 2014, we became acquainted with a care model that fulfilled these criteria. Project ECHO, which was pioneered at the University of New Mexico, uses telecommunications technology to connect PCPs with an interdisciplinary team of nationally recognized medical specialists in specific disease areas. These specialists remotely mentor and collaborate with PCPs to enhance their knowledge and clinical skills in these specific areas. Since its inception, Project ECHO’s model has been applied around the world to address many health conditions.

In 2014 we supported a pilot of a two-pronged application of Project ECHO to test this model’s feasibility in New Jersey. First, the model was used to enable PCPs to make greater use of multimodal nonopioid approaches—including behavioral health interventions—to treat chronic pain. The aim was to reduce the number of patients who might become opioid dependent in the first place.

Second, the model was applied to help PCPs improve their skills in prescribing buprenorphine, a Food and Drug Administration-approved medication for the treatment of opioid addiction. The aim was to increase the ease of access to, and efficacy of, substance use treatment for those who were already opioid dependent.

The eighteen-month project was conducted by the Connecticut-based Weitzman Institute in three New Jersey safety-net, primary care practices. We learned from its findings that the Project ECHO approach to improve pain management was feasible. PCPs were eager to participate and receive the support of a team of experts.

We also learned that buprenorphine treatment could be successfully integrated into primary care practices in New Jersey and that it reduced opiate misuse by already-dependent patients.

Based on these and other findings, we deemed the pilot a success.

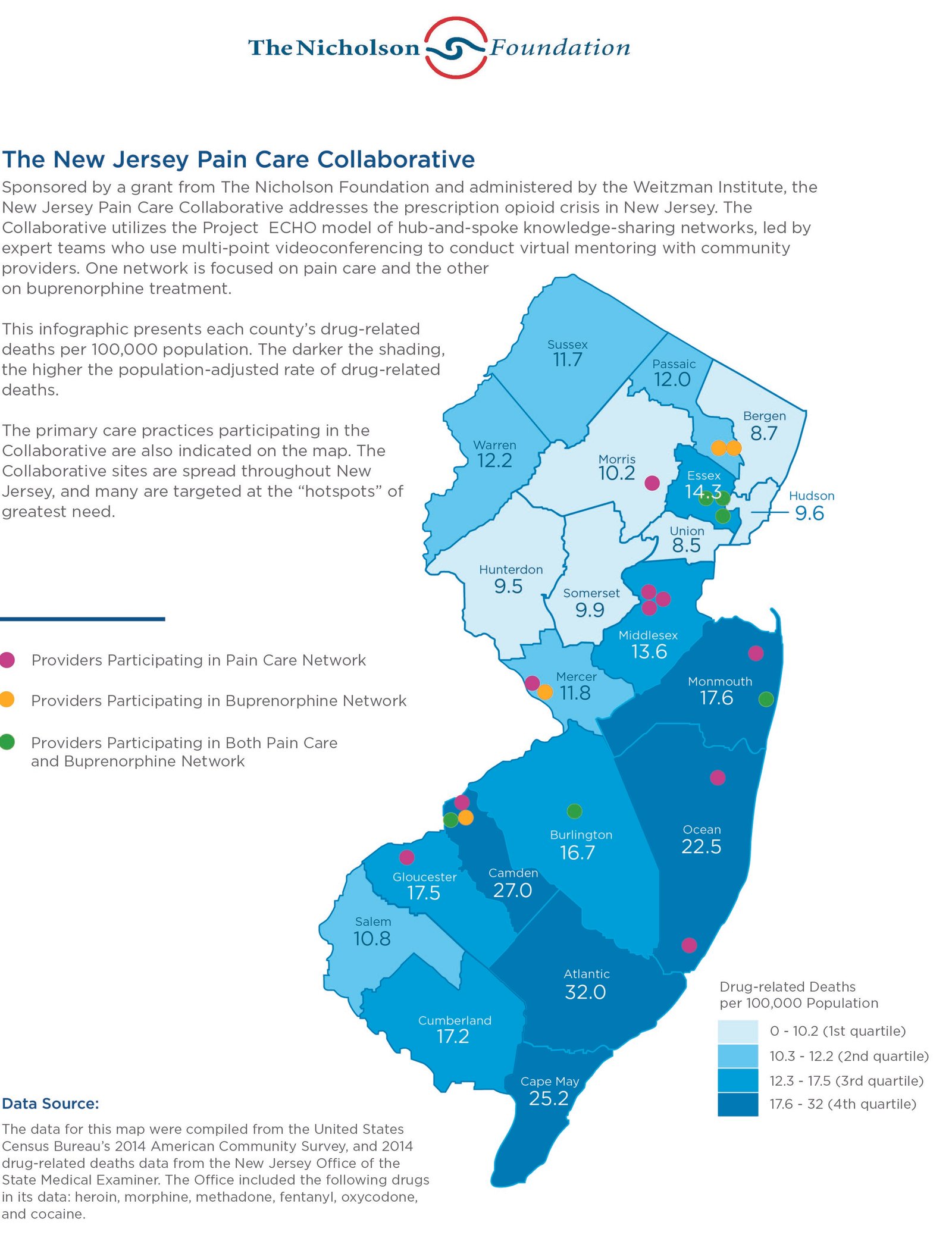

Consequently, as of July 2016, we have funded the Weitzman Institute to operate the New Jersey Pain Care Collaborative, which expanded the model to twenty-nine PCPs in twenty safety-net practices across the state. The majority of the participating practices are located in areas with the highest opioid-overdose death rates.

The overuse of prescription pain medications to treat chronic pain is clearly an urgent concern, both nationally and in New Jersey. Although it can be addressed in a variety of ways, it is essential that efforts focus on primary care practices and providers.

Around the country, states are implementing practice-level approaches that educate PCPs about the potential dangers of over-prescribing opioids, urge or require use of prescription drug monitoring programs, and encourage PCPs whose opioid prescriptions exceed accepted levels to change their prescribing practices, if appropriate. These approaches improve current prescribing patterns. However, they do not fundamentally alter the fragmented care provided to the millions of patients whose chronic pain involves aspects of both behavioral and physical health.

We believe a more comprehensive approach to pain care represents a key opportunity to have a long-term impact on the primary care system. This approach entails helping PCPs understand pain as a critical nexus where behavioral and physical health issues intersect. Treating this nexus holistically, as a component of whole-person care, can lead to overall changes in practice patterns if PCPs also apply this treatment approach to the way they address other medical conditions that involve aspects of both behavioral and physical health. These include such conditions as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which are among the largest cost drivers of our health care system. We suggest that groups that are interested in fostering systemic change within the primary care setting, including foundations, government agencies, and health plans, could benefit from what we are learning through our work on the New Jersey Pain Care Collaborative: Models that work collaboratively with PCPs to comprehensively address a specific health issue can also be catalysts for broader primary care transformation.

Related reading on Health Affairs Blog:

Benjamin Miller, “Creating A Culture Of Whole Health: A Realistic Framework For Advancing Behavioral Health And Primary Care Together,” GrantWatch section, April 14, 2016.

Joan Randell and John Jacobi, “State Licensing And Reimbursement Barriers To Behavioral Health And Primary Care Integration: Lessons From New Jersey,” GrantWatch section, April 7, 2016.

Becky Hayes Boober and Rick Ybarra, “Advancing Integrated Behavioral Health Care In Texas And Maine: Lessons From The Field,” GrantWatch section, August 11, 2015.

David Barash, “Project ECHO: Force Multiplier For Community Health Centers,” GrantWatch section, July 20, 2015.