On March 1, 2016, we published an article in the BMJ showing how in the US nearly $3 billion will be spent on discarded cancer drugs this year because companies package drugs in vials that contain too much of the drug for most doses, creating expensive leftover product. We proposed that companies in the US should either package drugs in more appropriate vial sizes to reduce the leftover amounts, or provide refunds for leftover drug.

Since the time of our article’s publication, numerous Senators have written letters to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) urging action on vial sizes, and calling for the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (HHS OIG) to investigate which companies sell their drugs in smaller vials outside the US than they offer to US patients. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has also mandated that beginning July 1 2016, all health professionals billing for infused cancer drugs (and other Part B drugs) to distinguish between claims that are for drugs that a patient actually receives and those claims that are for leftover drug.

On May 11, however, Health Affairs Blog published a post by Professors Sherry Glied and Bhaven Sampat projecting that although the waste we identified is a sizable problem, the solutions we offered may be incomplete.

One of Glied and Sampat’s concerns focuses on our suggestion that manufacturers should distribute their drugs in vial sizes that more closely match the doses that patients need. While they do not dispute that doing so would reduce the amount of the costly drug that is leftover after each dose, they worry about the presumption underlying this strategy.

Specifically, our argument presumes that the added cost of manufacturing and distributing another smaller vial size would be offset by the savings manufacturers would enjoy from having to make less of the drug. Glied and Sampat believe the opposite, writing that “it might be [less costly for manufacturers] to ship in a limited number of vial sizes and allow the excess drug material to be wasted.”

If they are correct, the other policy approach we proposed addressed the concern, as we stated that manufacturers could ship in limited vial size choices but then offer refunds for unused drugs if they preferred. Patients and insurers would save under either approach.

Drug Costs versus Vial Costs

That said, Glied and Sampat’s guess about the cost of drug versus cost of vial manufacturing may be incorrect. The drugs in our study are predominantly biologics, not small molecules. Manufacturing costs can be substantial. When Immunex and Genentech were exclusively manufacturing biologic drugs in the 1990s, they reported manufacturing costs of around 30 percent and 18-19 percent of total sales, respectively. Today Amgen, one of the most established biotech companies in the world, reports spending 20 percent of total sales on manufacturing expenses.

Meanwhile, vials themselves, are cheap to manufacture. A vial of the chemotherapy agent, cytarabine, is reimbursed at $0.88 by Medicare — that is for both the drug and the container it comes in. This implies that in this and other cases, the vial alone costs less than that. Data on vial size choices show that selling different size options is also viable — Hospira sells 4 different vial sizes of Cytarabine. To put these data in perspective, we proposed adding a single new vial size for each of 18 of the 20 drugs in our analysis (and none for the other two); the average Medicare reimbursement for the drugs in the new vial sizes would be around $462.

A Different Kind Of Market

Glied and Sampat also state that pharmaceutical companies will hike prices in response to any policy that reduces their ill-gotten revenue from the wasted drug. But this speculation ignores both the political economy that affects drug prices and empiric data.

Their theory is that drug prices are anchored to insurers’ and patients’ “willingness to pay.” This term poorly describes the cancer drug market, in which Medicare has a legal requirement to pay for drugs at the price the manufacturer sets, and physician prescribers make larger mark-ups the more a drug costs (hence their willingness rises rather than falls as price rises).

But more important, Glied and Sampat have misunderstood why companies would prefer having more excess volume of the drug in the vial over raising their prices. First, they can publically present in press releases and sponsored pharmacoeconomic analyses that their drug has one price (based on only the patient dose) but actually recoup a higher amount per treatment due to leftover drug that is also in the vial (in all cases these drugs are reimbursed per unit of the drug in a vial, so 10 mg of drug costs exactly twice as much as 5mg of drug).

A recent review of cost effectiveness analyses ?of cancer drugs shows, in fact, that most pharmacoeconomic analyses do not incorporate leftover drug into their drug cost calculations which led cost effectiveness ratios to appear falsely favorable. Drug companies are aware of this, as the analyses they submit to the United Kingdom National Institute for Clinical Excellence are required to include the cost of leftover drug, not just the cost of the patient’s dose. We doubt, then, that it is a coincidence that vials of bortezomib and pembrolizumab, two cancer drugs in our analysis, contain 1 mg and 50mg respectively in the UK market, while in the US they are 3.5mg and 100mg. The UK vial sizes lead to less waste per dose.

Another more problematic reason why companies might add excess drug to their vials can be found in past Department of Justice settlements. These include a case where drug was added to the vial so that doctors could pool the leftover and generate an extra reimbursable dose of drug without having to buy it, and another where a company systematically scheduled drug dosing to increase the revenue from leftover.

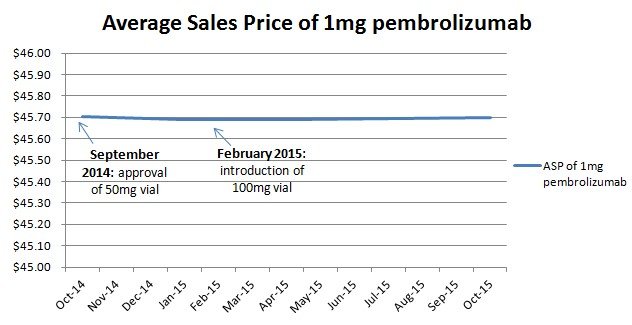

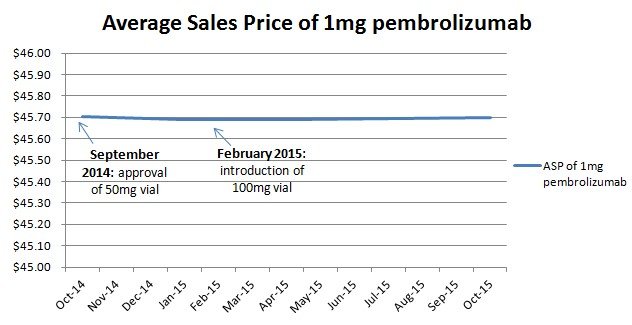

Lastly there is empiric data contradicting Glied and Sampat’s speculation. In February 2015, Merck replaced the 50mg vial of Keytruda (pembrolizumab) with a 100mg vial in the US market, raising the amount of waste per treatment. Glied and Sampat would predict that Merck would then lower their price per unit to achieve the same price per dose. But they did not (Figure 1).

Figure 1

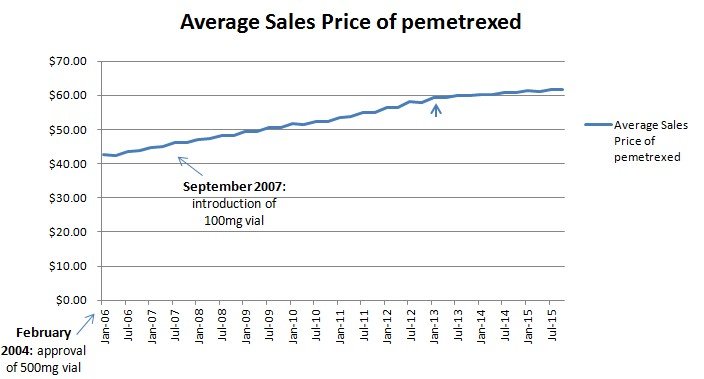

In September 2007, Eli Lilly introduced a smaller 100mg vial to accompany their 500mg vial for their drug Alimta (pemetrexed), reducing the amount of waste per treatment. Glied and Sampat would predict that the company would then raise their price per unit, but the rate of price increases seem unaltered (Figure 2) over that time period (the second small arrow points to the implementation of sequestration which lowered the reimbursement mark-up and thus slowed price inflation of infused cancer drugs as we detailed in a set of reports on CMS’ proposed Part B pilot).

Figure 2

While we appreciate the thoughtful critique of our analysis from Glied and Sampat, we disagree with their conclusions. Policymakers should consider either ensuring that drugs are packaged in a manner that reduces waste, or require that companies give refunds for leftover drug. This way payers and patients will not continue to spend billions of dollars on drugs that are ultimately discarded.